Home | Novidades | Revistas | Nossos Livros | Links Amigos Pieper's Theory of Feasting -

the Work of a "Brasiliano" Painter

Jean Lauand

Fac. Educ. Univ. de São Paulo

jeanlaua@usp.br

(English translation by Alfredo H. Alves)

"Wozu Dichter in dürftiger Zeit?" (Hölderlin)

"I love human beings; or to put it more clearly,

I love the divine that dwells in every human being" (F. Pennacchi)

In 2002 it will be ten years since Fulvio Pennacchi (27-12-05/ 5-10-92), the most Brazilian of the great Italian painters, passed away. The year 2002, then, will be an appropriate year in which to reflect again on the unique significance of his art in the contemporary world; an art which is the full realization of the classical theses of the philosophy of art.

Retaining all the time his solid Italian formation, Pennacchi was at the same time profoundly Brazilian: not only because he lived sixty-three of his eighty-seven years in this country, but mainly because his emigration brought him to a country whose simple folk live (or used to live) these realities and values with a spontaneity which is exactly in tune with his specific artistic sensibilities: simplicity, the sense of brotherhood, friendliness, "fiesta", love. Pennacchi identified himself with the Brazil that furnished him with raw material for an original art and an art of great profundity; his paintings are like delicate "chorinhos" (a type of popular song, typically Brazilian) written by a classical composer.

With all justice, Pennacchi is remembered as one of the principal names in the History of Art in Brazil. Among other things, he is well known for his mastery of various techniques and for his participation in the Grupo Santa Helena that gave a new impetus to Brazilian painting in the 1930's. The purpose of this paper, however, is to point out that the significance of Fulvio Pennacchi's art resides in the assumptions underlying his work, assumptions that have everything to do with the classical Philosophy of Art. In short, to relate Pennacchi's art to the fundamental theses of Pindar, Hölderlin, Plato and Thomas Aquinas. In such a view of the world, art is especially related to feasting, creation, love, praise, participation and contemplation.

Let us begin with the disconcerting misgivings which Hölderlin gives voice to: "Why are the arts dying? Why are the theatres mute? Why is the dance at a standstill? ". It is not by chance that another verse in the great poem "Brot und Wein" - in its way a treatise on the Philosophy of Art - inspired aesthetic studies by two of the greatest contemporary German philosophers, Heidegger and Pieper.

This decisive verse, which diagnoses in depth not only the perplexity of art but also the perplexity of contemporary man is: "What is the use of poets in times of penury?". Hölderlin's answer to this tragic question places him in the same line of the conception of art as that affirmed 2,500 years ago by Pindar, and which is the only argument that enables us to fully understand Pennacchi's greatness.

The greatness of the artist is, in Pennacchi's case, wholly (in its absolute sense) linked with the greatness of the man: In one's contacts with Fulvio, what always, unchangingly, transpired was the deep unity -- a rupture with the penury of our days! -- between his way of being and the force of his artistic expression: all are enchanted by his art, although not all can give the reason for their enjoyment. For Fulvio Pennacchi imbued his art with the values which he held; and these values are the more significant for our times in that they are difficult not only to live by, but to understand.

Such a difficulty lies, above all, in the right understanding of the meaning of the penury of our times: "Our times," says Heidegger, on commenting Hölderlin's verse, "hardly understand the question; so how can we understand the answer given by Hölderlin?". This answer goes right to the heart of the Great Tradition of aesthetics: true art. in the last analysis, can only flourish as the affirmation and the praise of God for creating such a beautiful world: "Ah, my friend, we have arrived too late... Yes, there may still be gods, but they are above us, in a world that is alien to us ... What can I say? I don't know. What is the use of poets in times of penury?".

In our days, penury has come to such a extreme state, says Heidegger, that we are not even able to see that the absence of God is an absence. For penury is not material lack, but the absence of God "for us". God may even exist but "in anderer Welt", in another world, alien to us.

This way of viewing art has, as we have said, historical roots: in the Hymn to Zeus, Pindar says that when Zeus had completed his work of ordering the world, he asked the other gods if anything was missing. And the answer was: "Yes, where are the god-like creatures to praise the beauty of the Cosmos?". It is only when the world is seen as a creation -- as something wrought by God, ever-present and upholding -- and when man is seen as sharing in what is above him -- that the muses can arise to celebrate a world full of meaning and beauty.

It is beyond the consumist mentality of our days, bitter and complaining all the time, of people who are so self-sufficient in a technologically domesticated world that has eyes only for "special effects"; it is beyond their capacity to perceive the subtle simplicity of the values we are talking about. The charm of Pennacchi's works is the fruit of a great technical and artistic talent which expresses the classic view of the world. His paintings are, in this way, a kind of existential therapy for the multi-faceted neurosis of our days that insists on its error of considering "fiesta", praise, love and creation expendable.

Pennacchi's paintings are an invitation to overcome this penury, the first manifestation of which, as Hölderlin says, is to be incapable of feasting.

As Plato says in his Laws, the muses are a gift of divine mercy given to men as partners in feasting and an antidote to that dullness of the spirit to which we have been subjected. And in times of penury we can ask with Pieper: "What is the use of company in feasting when there is no feasting?". For, Pieper continues, the festive attitude can exist only for those who are deeply in tune with the world and at one with God: what would be the use of poets (and painters) if not to sing and celebrate a world that was not a Creation? Feasting is always praise and agreement. Anyone who celebrates a feast, even a simple birthday party, gives consciously or unconsciously, his assent to God and the world. Or would it be possible for anyone who is seriously convinced, like Sartre, that "it is absurd to have been born, it is absurd that we exist" to celebrate a birthday party?

For feast and art are nourished by love, which is after all approval, affirmation -and as Pieper felicitously puts it - to be with one's beloved and to say " How good it is that you exist! How wonderful, that you are in the world!"

Human love, however, is something provisional; as a matter of fact it is a continuation, a participation, an extension of another Love: the love of God, which since the very beginning utters the creative sentence: "It is good that you exist."

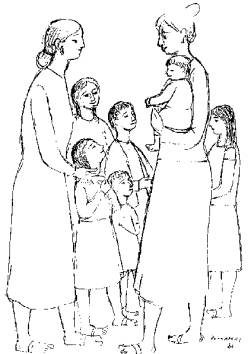

Pennacchi shows precisely the created character of the world; in simple everyday scenes he shows the presence of God in that reality that is around us. I am not speaking of his wonderful sacred art but the human reality in the everyday world he sees and induces us to see: work, popular "fiestas", water, lovers, a mother embracing her child, simple people living together, birds, dogs -even they are infected by the atmosphere of love between human beings-, children playing...

Pennacchi shows us the value of simplicity, the richness in a good, simple, Brazilian, soul, at one with God and with the world, ever ready to turn to his neighbour with the frank, open look which declares: "How good it is that you exist!"

What can be seen in his human figures and landscapes is tenderness, love and welcome -human love, an extension of the creative Love of God. Guided by Pennacchi's eye we perceive in this ordinary reality something new, or rather something seen but which has not sunk in, something erased by the day-to-day penury under which we live; all that is, is good, is loved by God. And not only this: it is because it is loved by God.

Needless to say, as with all the classics, Pennacchi is not blind to the harsh realities of life, nor are his eyes closed to evil or the great social problems of our times; in other words, art is not for him an escape. In this respect we may be permitted to quote Louis Armstrong's introduction - a sort of testament - to the song "What a Wonderful World!":

Some of you, young folks,

been saying to me:

"Hey Pops! What you mean

`What a wonderful world?'

How about all the wars all over

the places you call them wonderful?

And how about hunger and pollution?

That ain't so wonderful either!!"

How about listening

to Old Pops for a minute:

Seems to me it ain't the world that's

so bad but what we're doing too it

And all I'm saying is: See what

a wonderful world it would be if only

we'd give it a chance.

Love, baby, love! That's the secret!

yeaaahh! If lots more of us love each

other we'd solve lots more problems

and this world would be bettah...

That's what Old Pops keep sayin'...

I see trees of green, red roses too (...)

And I think to myself: `What a wonderful world!'"

To draw attention to this secret is the mission of the artist. As Pieper says: earthly contemplation pressuposes the conviction that, in spite of all, there is peace, salvation and glory in the very depth of each thing; that nothing or nobody is really lost; that in the hands of God, as Plato says, are the beginning, the middle and the end of all things.

With all this we have come to the core of the classical philosophy in Pennacchi's art: the metaphysics of participation. Participation, in its true meaning, is to have as opposed to to be: metal has heat, said the ancients, in the measure which it participates in the heat that fire is. Creation is the act in which being as participation is given to us. And so, all that is, is good: it participates in Being (and the Good). In this way, Aquinas's sentence: "In the same way as created good has a certain similitude to and participation in Uncreated Good, so the obtaining of any created good is also a kind of participation in everlasting Happiness" is the foundation not only of metaphysics, but also of aesthetics.

But "obtaining a good" is, as Aquinas says, fundamentally contemplation: to behold with love: "The contemplation of God in Creation is already the beginning of the happiness which will be consummated in Heaven".

The art of Fulvio Pennacchi, the aesthetics of participation, opens up to us, with its colours, the beginning of Heaven, which is the contemplation of earthly things.

The life and art of Fulvio Pennacchi makes us understand participation and the meaning of Guimarães Rosa's dictum: "The flower of love has many names". And leads us to discover, to quote Rosa again: "the Who of things".